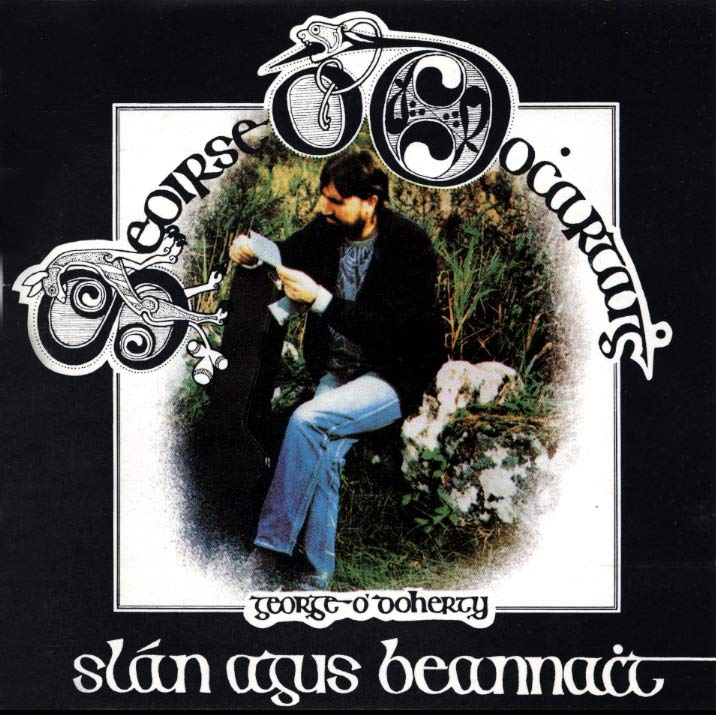

Description

NOW OUT OF STOCK

(but soon available as mp3 downloads)

[Goodbye and Blessings]

Irish Folk

- The Tinker’s Daughter

- Slán agus Beannacht [Goodbye and Blessings]

- An Réaltán Leanbach [The Child-like Star]

- Cúl na Cruaiche [Behind the Hay-stack]

- Morgan Magan [by Carolan]

- Seoladh na nGamhna [Driving the Calves] / As I Roved Out

- Cuach Mo Londubh Buí [Cuckoo, My Yellow Blackbird]

- Mary from Dungloe

- Brian Boru’s March

- When Two Lovers Meet

- My Cavan Girl

- Sadhbh Ní Bhruinngheala [Sive O’ Brannelly]

Slán agus Beannacht [Seoirse Ó Dochartaigh] Errigal SCD003 [1988]

The Tinker’s Daughter

A song collected in the 1940s in Co. Kerry by the Anglo-Irish composer E. J. Moeran. He spent several weeks with the traveling people sometimes living in tents with them listening to their songs. Moeran’s cycle of “Irish Songs from Co. Kerry”, which includes a version of “The Tinker’s Daughter”, was published in1950. The chorus is probably cant or shelta – the secret slang of the traveling people.

I am indebted to Donegal banjo player Pól Mac Grianna for the excellent choice of the jig “The Cliffs of Moher” as a companion piece to the song.

If you’re a tinker’s daughter

As I took you for to be,

Will you ride up to Kilgarvan

Making buckets there with me?

Chorus: With me gumshala and me gooshala,

And me gashala-la callerio,

Me gooshala and me gumshala,

Wallap-i-dout my hero.

Before we went to Kenmare

We hadn’t this nor that,

But now the fair is over

We’ve a piebald and a flat.

I soldered in the stable

And I soldered in the hall;

The children in the kitchen

Threw away me tools and all.

Sure I can make a bucket,

And I can make a pike,

I can do a job o’ tinker’s work

The darkest hours of night.

Sure I’ll pull out me pony

And I’ll try to make a swap,

I’ll catch the tinker’s daughter

And I’ll catch her on the hop.

Slán agus Beannacht le Buaireadh an tSaoil

(Goodbye and Blessings to the Sorrows of the World)

Probably one of the best known of the macaronic songs [alternating Gaelic and English lines]. This one originated in the Mayo/Galway region where it was noted down by Mrs. Costello and printed in her collection Amhráin Mhuighe Seóla [1919].

The language in love-songs of this kind belongs to the romantic Western World of J. M. Synge. This one evokes in a succession of colourful images the cruel hardships of 18th and 19th century rural Ireland, a society consoled only by an imagination both powerful and dramatic. It was all they had really to keep them from falling into the abyss of poverty.

I’ve neither wheat nor potatoes nor anything,

Nár fiú an pluid leapan bheadh tharainn ‘san oích’.

(Nor even a bed-cover to throw over us in the night)

Greg and his wife Deirdre really immersed themselves into this song. Deirdre’s sensuous string playing underscores the whole music arrangement.

One morning in June agus mé ‘ghabháil a’ spaisteoireacht

Casadh liom cailín ‘s ba ró-dheas a gnaoi,

She was so handsome gur thit mé i ngrá léi

Is d ‘fhág sí an arraing trí cheartlár mo chroí.

I asked her her name nó cad é an ruaig bheannaithe

A chas ins an áit thú, a ghrá ghil mo chroí?

My heart it will break if you don’t come along with me,

Slán agus beannacht le buaireadh an tsaoil.

Maise, cailín beag óg mé ó cheantar na farraige,

Tógadh go cneasta mé i dtosach mo shaoil.

I being so airy ós é siúd ba chleachtach liom

Which made my own parents and me disagree.

Maise, a chuisle ‘s a stór, ach an éistfeá liom tamallt

I’ll tell you a story a b’ait le do chroí

That I’m a young man who is deeply in love with you,

Surely my heart is from roguery free?

Go you bold rogue, sure you’re wantin’ to flatter me,

B’fhearr éan i do láimh ná dhá éan at a’ chraoibh,

I’ve neither wheat, nor potatoes, nor anything,

Nár fiú an pluid leapan bheadh tharainn ‘san oích’.

Ceannóidh mé tae dhuit is gléas maith in aice siúd

Gúna English Cotton den fháisiún ‘ta daor;

So powder your hair, love, and come away ‘long with me,

Slán agus beannacht le buaireadh an tsaoil.

There’s an alehouse nearby agus beimid go maidin ann,

If you are satisfied, ‘ghrá ghil mo chroí,

Early next morning we’ll send for the clergyman,

Beimid (a) ceangailte i nganfhios don tsaol.

Beimid ag ól ‘fhad a mhairfeas an t-airgead,

Then we will take the road home with full speed.

When the reckoning is paid, who cares for the landlady?

Slán agus beannacht le buaireadh an tsaoil.

An Réaltán Leanbach

(The Child-like Star)

The arrangement of this traditional song from Clear Island, Co. Cork, is an adaptation of a version for voice and piano which Seán Ó Riada made in the late 1950s. The dance-tune used here by way of a ritornello is one that fascinated Ó Riada for years – The Garden of the Daisies. He used to play it not only as a solo piano piece, with exquisite ornamentation, but as a tune that ingeniously harmonises with the song Iníon a’ Phailitínigh [The Palatine’s Daughter].

An Réaltán Leanbach is close to the armour courtois type of song very popular all over Europe in the Middle Ages. But it differs slightly in that it has its roots in an even earlier Irish tradition of the invitation song where the man tries to entice his lover to a land of enchantment.

Ó ‘sé mo lean gan mé agus í!

I ngleanntán sléibhe nó ar mhaol-chnoc fraoigh

(Isn’t it a pity that she and I

Cannot be in a mountain valley or on a small

heathery hillside).

My old pal Peadar Mac Ardghail recorded this with me in one take – no rehearsals. He sat in the recording booth, strapped on his accordion, closed his eyes, and let it all happen!

Tá an Réaltán Leanbach sa tír lastuaidh,

Tá gile agus finne le fáil ‘na gruaidh.

Tá a píob mar a’ sneachta agus í ‘na suan,

Is gur binne liom a glao ná géim ón chuaich.

Ó ‘se mo léan gan mé agus í,

I ngleanntán sléibhe nó ar mhaol-chnoc fraoigh,

Mar ar bh’eol dúinn cluiche, nó stró beag imirt,

A bháibín na finne, dá dtéadh siúd linn.

‘Sí an Réaltán Leanbach do ghrás ar dtús,

Is fíor gur thugas taithneamh dí thar mhná na Mumhan,

Is dá mbéinnse marbh is an bás im chionn –

Is a rún, ná tréig mé ach éalaigh liom.

Ná leigse chun fáin mé mar chách ar siúl,

‘S gurbh aoibhinn an lá a bhéinn sealad agus tú,

A Róis gan dearmad, beir scéala cruinn abhaile uaim,

Go n-éalochadh an cailín deas thar sáile liom.

Cúl na Cruaiche

(Behind the Haystack)

This song, as far as I am aware, has not been heard anywhere outside the Gaeltacht of Ranafast, an area extraordinarily rich in folk and literary traditions. It lies on the rugged north-west coast of Donegal.

I heard the song from the singing of Hughie Phadaí Hiúdaí (Aodh Ó Dhuibheannaigh) who died tragically after a road accident in 1986 – go ndéanaí Dia trócaire air. Hughie had an outstanding memory and a vast store of songs and stories but couldn’t recall where he heard this particular one. It’s a love-song of unusual intensity; words and music, to quote the well-known phrase, “melt into one another”.

Nuair a d’fhiafraigh mé do Hughie an raibh an t-amhrán seo á cheol ag seandaoine Rann na Feirste anois, dúirt sé “Cé hiad na seandaoine anseo ach mise!”

I dedicate this song to the people of Ranafast whose songs touch the very soul of Ireland. Go raibh fada buan sibh!

Bhí mé i gcúl na cruaiche an uair údaí mé ‘gus í;

Cuireadh Ó! ní bhfuair mé ‘s nach truaillith’ mar rinneadh an

gníomh.

Goidé an gar a bheith da lua liom níl suairceas le fáil mar ‘bhí

Ó’s ort-sa a cuireadh an chluain ó ní bhfuair tú do chailín saor.

Nach mór a’ cúrsaí bróin domhsa dólais is tuirse croí

Mo chailín a bheith dá pógadh ag smóilín a’ bhrollaigh bhuí,

Ó cuirim-se dith bróin ar an óig-mhnaoi nár fhan mar bhí

‘S gur mise ‘ghabhfadh an ceol dí san fhómhar má b’fhada an

oích’.

Is deas a’ bhean mo ghrá-sa ‘s ró-dheas a cos ‘s a ceann,

A súil ghorm, a gáire ‘s a dhá cích bhí corra cruinn;

Ó thug sí an “sway” ar mhná deas’ ó Árainn go Dún na nGall

‘Sa dá mbínn-se ‘gabháil thar sáile is í Máire ‘bhéinn ‘iarraidh liom.

Ó thug mé grá don óig-mhnaoi ‘s níor éirigh liom á fáil go fóill,

A’ dara grá dá béilín ‘s a cúl buí ar dhath an óir.

A’ tríú grá níor fhéad mé gan mo ghruaidh a bheith ‘ sileadh deor;

Nach é mo léan a chéad-searc gan mé ‘gus tú seal ag ól.

Morgan Magan

(Carolan)

“Morgan Magan” was written by the blind Irish harper/composer Turlough O’Carolan (1670-1738) in honour of the youngest son of the Magan family of Clooney, Co. Westmeath. In the 18th century many blind people eked out a livelihood by becoming itinerant harpers playing for the rich patrons in the ‘Big Houses’ of the Anglo-Irish.

Carolan was a poet as well as a harper and many of his ‘planxties’ have words associated with them (to be sung or recited). It is of social and historical interest to note that only one praise-poem out of over 200 compositions was written in English. We may conclude from this that the Anglo-Irish understood and probably spoke Irish as a second language.

The eloquent “Morgan Magan” shows the extent of Carolan’s musical influences: Italian Baroque and native Irish harp music. Italian music was very much in vogue in Ireland at the time, the music of Corelli in particular. Another well-known Italian composer, Geminiani, spent many years in Dublin.

As I Roved Out

My friend Pól Mac Grianna gave me this song. Since the very early Clancy Brothers rendering the song has not, to my knowledge, been re-recorded. Nor has it been subjected to the usual over-exposure that sometimes kills popular folksongs. I tried to capture here something of the song’s original freshness. As a prelude (played on a B-flat whistle) I have chosen the Munster version of the Gaelic Pastourelle “Seoladh na nGamhna” (Driving the Calves). “As I Roved Out” is a variant of this tune.

Pól’s banjo work and Harald’s bodhrán just did the trick!

As I roved out on a May morning,

On a May morning right early,

I met me love upon the way,

Well Lord, but she was early!

chorus: And she sang little-dootle, little-dootle,

little-dootle-dee, and she hyddle-dittle-dee,

And she hyddle-dittle-dee and she landed.

Her boots were black and her stockings white

And her buckles shone like silver,

She had two dark and rovin’ eyes

And her earrings tipped her shoulder.

I went to her house on the top of the hill

When the moon was shining clearly,

She arose to let me in

But her mammy chanced to hear me.

She caught her by the hair of the head

And down to the room she brought her,

And with the butt of a hazel twig

She was the well-bate daughter.

Will you marry me now, me soldier lad,

Will you marry me now or never?

Marry me now, me soldier lad,

For you see I’m done forever.

I can’t marry you, me bonnie wee lass,

I can’t marry you, me honey,

For I have got a wife at home

And how could I disown her?

A pint at night is my delight

And a gallon in the morning,

The oul women has my heart broke

But the young ones is me darlin’.

Cuach mo Londubh Buí

(Cuckoo My Yellow Blackbird)

The historical background to this song in some ways justifies the treatment given to it here. A variant of the tune appears in Edric Connor’s Songs of Trinidad [1958]. In this collection it is none other than the traditional West Indian Lord’s Prayer with chorus & drums. Connor learned it from a religious group known as The Shouters. How did this come about? A Gaelic song ending up as a Negro spiritual?

It would appear that some of the Cromwellian deportees, who arrived in the West Indies from Ireland in the 1650s, brought with them some of their Gaelic songs. Cuach Mo Londubh Buí would have been one such song as it was extremely popular all over Ireland at the time. Indeed, the Co. Tyrone version is very close to the Trinidad song – some phrases correspond note for note.

The words of the Gaelic version, if they have any significance at all, are anything but religious. They tell of the fickleness of women and of a strange, magical creature called gruagach an óir bhuí [the hairy giant of the yellow gold] who seems to be calling all the shots.

For afficionados of folk music the chorus translates as follows:

Cuckoo today and cuckoo tomorrow,

Cuckoo my yellow blackbird,

Cuckoo every day after till the end of the season,

Cuckoo my yellow blackbird.

When I first introduced the song to Greg Scanlon, the producer of the album, he immediately said “Beach party!” So we got out the marimba and a couple of beer glasses and got partying right away!

Bhí mise is mo bhean bheag lá gabháil a’ bóthar,

‘s óró ‘ghrá mo chroí,

Is cé chasfaí dúinn ach gruagach an óir bhuí,

Cuach mo londubh buí.

D’ fhiafraigh sé domhsa an ‘níon domh an óigbhean,

Is dúirt mé féin gurbh í mo bhean phóst’ í.

Curfá:- Cuach inniu a’s (a) cuach amárach,

Cuach mo londubh buí,

Is cuach i ndiaidh achan lá go ceann ráithe,

Cuach mo londubh buí.

“A’ dtabharfaidh tú domhsa choíche go deo í?

Mur ndéanfaidh tú sin liom déanfaidh mé cóir leat”.

“Gabh tusa na mullaigh ‘gus mise na móinte,

Is cibé fear ‘ leanas sí bíodh sí go deo aige.

Chuaigh seisean na mullaigh ‘gus mise na móinte,

‘gus lean sí an gruagach nó b’aige bhí an óige.

Phill mé ‘na bhaile go buartha cráite,

Is luí mé síos ar mo leaba trí ráithe.

Mary From Dungloe

This famous Donegal song is taken from Colm Ó Lochlainn’s “Irish Street Ballads” (1939) where he states that it was given to him by an Ardglass fisherman in 1913. It was a big hit for a group of the “Ballad Boom” called Emmet Spiceland and has worn the years well. I became interested in it again when some American friends convinced me that there was more to the song than met the eye. They pointed out to me its beautiful melodic leaps and its directness of expression. “Mary” is a bit like “Danny Boy”; you can never quite kill it although you often hear it being murdered in lounge bars.

Oh then, fare thee well, sweet Donegal, the Rosses and Gweedore,

I’m crossing the main ocean where the foaming billows roar;

It breaks my heart from you to part, where I spent many happy days;

Farewell to kind relations, I am bound for America.

Oh then, Mary, you’re my heart’s delight, my pride and only care,

It was your cruel father would not let me stay there;

But absence makes the heart grow fond, and when I am over the main,

May the Lord protect my darling girl till I return again.

And I wish I was in sweet Dungloe and seated on the grass,

And by my side a bottle of wine and on my knee a lass;

I’d call for liquor of the best and I’d pay before I would go,

And I’d roll my Mary in my arms in the town of sweet Dungloe.

Brian Boru’s March

“Brian Boru’s March” has become something of a favourite among harpers of the present-day revival. Significantly, it was this tune that the Dundalk harpist Patrick Byrne played during the last recorded performance (c.1860) of aurally transmitted Irish harp music. This tradition lasted well over 1000 years.

Despite the title, the tune is unlikely to be as old as the battle it commemorates. The Battle of Clontarf took place just outside Dublin in 1014 AD when King Brian defeated the Norsemen.

(On the LP I dedicated this march to the Behans and Reillys of Dublin who encouraged me so much during our student days when I used to play it in bed-sits all around the city)

When Two Lovers Meet

I first heard this song being sung by Dolly McMahon, a Galway singer with a great feeling for the “sean-nós” (old-style singing). It’s obviously a Cork song with the reference to the River Lee. The tin-whistle piece which precedes it is called “The Lament of Staker Wallace” but I understand that the correct (older) title is “Bean Dubh an Ghleanna” (The Dark-haired Woman of the Glen) which suits the subject-matter of the song perfectly.

When two lovers meet down beneath a green bower,

When two lovers meet down beneath a green tree,

When Mary, fond Mary, declared to her lover:

“You have stolen my poor heart from the banks of the Lee.”

Chorus: I loved her very dearly, so true and sincerely,

There was no-one in this wide world I loved better than she;

Every bush every bower, every sweet Irish flower,

Reminds me of my Mary on the banks of the Lee.

Don’t stay out late, love, on the moorlands, my Mary,

Don’t stay out late, love, on the moorlands from me,

How little was our notion when we parted on the ocean,

That we were forever parting from the banks of the Lee.

I’ll pluck her some roses, some bloomin’ Irish roses,

I’ll pluck her some roses, the fairest ever grew,

And I’ll place them on the grave of my own true-loving Mary,

In that cold and silent churchyard where she sleeps ‘neath the dew.

My Cavan Girl

(Thom Moore)

Thom Moore, an American musician who spent several years in Ireland playing with such groups as Pumpkinhead and Midnight Well, wrote this song. He won the Cavan International Song Contest outright one year with it.

The Irishness of the music owes something, I think, to the long, flowing lines that characterise many Gaelic songs. When I ran into Thom a few years ago, travelling from Shannon to Sligo, he told me that he had based the melody on The Lakes of Pontchartrain. But the ghost of the old ballad The Maid of the Sweet Brown Knowe is lurking around Thom’s melody somewhere! Nevertheless, Mr Moore has left us with a real gem!

As I walk the road from Killeshandra weary Isit down,

For it’s twelve long miles around the lake to get to Cavan Town;

Though Oughter and the road I go once seemed beyond compare,

Now I curse the time it takes to reach my Cavan Girl so fair

The Autumn shades are on the leaves, the trees will soon be bare;

Each red-gold leaf around me seems the colours of her hair;

My gaze retreats to find my feet and once again I sigh,

For the broken pools of sky remind me of the colour of her eyes.

At the Cavan cross each Sunday morning, there she can be found,

And she seems to have the eye of every boy in Cavan Town;

If my luck will hold I’ll have the golden summer of her smile,

And to break the hearts of Cavan men she’ll talk to me awhile.

So next Sunday evening finds me homeward – Killeshandra bound –

To work the week till I return and court in Cavan Town;

When asked if she would be my bride, at least she’d not said no,

So next Sunday morning rouse myself and back to her I’ll go.

Sadhbh Ní Bhruinngheala

(Sive O’Brannelly)

I first heard this song on a radio programme many years ago performed by a group of singers from Conemara during an “oíche airneáil” (social evening). The verses were taken up by various singers while the whole company joined in the chorus singing in unison. Songs of this kind (like “Cuach Mo Londubh Buí) belong to the medieval ‘carole’ or ’round-dance’ tradition (a combination of singing and dancing) which the Normans were supposed to have brought into Ireland. Although the practice of dancing to them died out, songs continued to be made in the same mould as the carole (not to be confused with the much later Christmas Carol) for centuries afterwards.

Sive, the girl in the song, is being bantered by the young men who, in a playful kind of way, discuss her dowry, or lack of it. Other suitors deliberate on their own wonderful skills, such as dancing, ploughing or sailing. She’s not impressed…. until a fisherman offers to bring her to Galway City in his boat… women !!! The jig-tune which weaves its way through the song is another Conemara air – “Cailleach an Airgid” (The Hag with the Money).

Ó cailín beag óg mé, cailín beag macánta,

Nár chuala sibh trácht ar Shadhbh Ní Bhruinngheala,

Curfa: Óra, ‘Shadhbh, ‘s a Shadhbh Ní Bhruinngheala,

A chuisle ‘s a stóirín, éal’ ‘gus imi’ liom.

Máistir báid mhóir mé ‘dhul ród na Gaillimhe,

D’fhliuchfainn trí fhód ‘s ní thógfainn aon fharraige,

Ó máistir báid mhóir mé is damhsóir cumasach,

Fear sluaiste is láí ar dhá cheann an iomaire.

Máistir báid mhóir go deo ní ghlacfad-sa

Nuair a thaganns an chóir is iondúil nach bhfanann sé.

Ní iarrfainn de spré le Sadhbh Ní Bhruinngheala

Ach Bail’ Inis Gé ‘s cead éalú ar choiníní.

Ní thógfainn go deo thú mur’ dté tú i dtrioblóid,

Gunna mór ‘fháil ‘s cead éalú ar choiníní.

Tá gúna breá nua ag Sadhbh Ní Bhruinngheala,

Cóitín beag donn gan ghabhal gan mhuinchille.

Nuair a thaganns lá breá is an ghaoth ón fharraige

Bhéarfa mé Sadhbh liom go Cuan na Gaillimhe.

Óra, ‘Shadhbh, ‘s a Shadhbh Ní Bhruinngheala

Comhairle do mháithrín, éal’ ‘gus imi’ liom.

MUSICIANS

Seoirse Ó Dochartaigh: lead vocals, harmony vocals, guitar, whistles, percussion.

Greg Scanlon: keyboards

Deirdre Scanlon: violin, viola

Peadar Mac Ardghail : vocal harmonies, accordion

Pól Mac Grianna: banjo

Harald Jüngst, bodhrán

Colum Sands, bodhrán,

Karen Russell: vocal harmonies.

PRODUCTION: Greg Scanlon

ENGINEER: Colum Sands

RECORDING: Spring Studios, Rostrevor, Co. Down

COVER DESIGN & INLAYS: Barry Britton

PHOTOGRAPH: Connor Sinclair

NOTES: Seoirse Ó Dochartaigh

(1988)