The Aisling [vision] poem is entirely unique to Gaelic Ireland. Poets in the 18th century, dispossessed of their former position as “poets in residence“, writing mainly poems of praise for the aristocratic houses, now took to producing poems of hope and vision. That hope and vision was for a Gaelic Ireland fully restored with political autonomy and cultural freedom. These were poets of great learning and skill who could introduce at will any classical allusion from Greek and Latin mythology which took their fancy, but were also thoroughly versed in native Irish legends, poetic forms and elaborate rhyming schemes. They also did something quite remarkable: they set their poems to magnificent tunes: song-airs that had been popular at the time, but also new melodies in the Irish style.

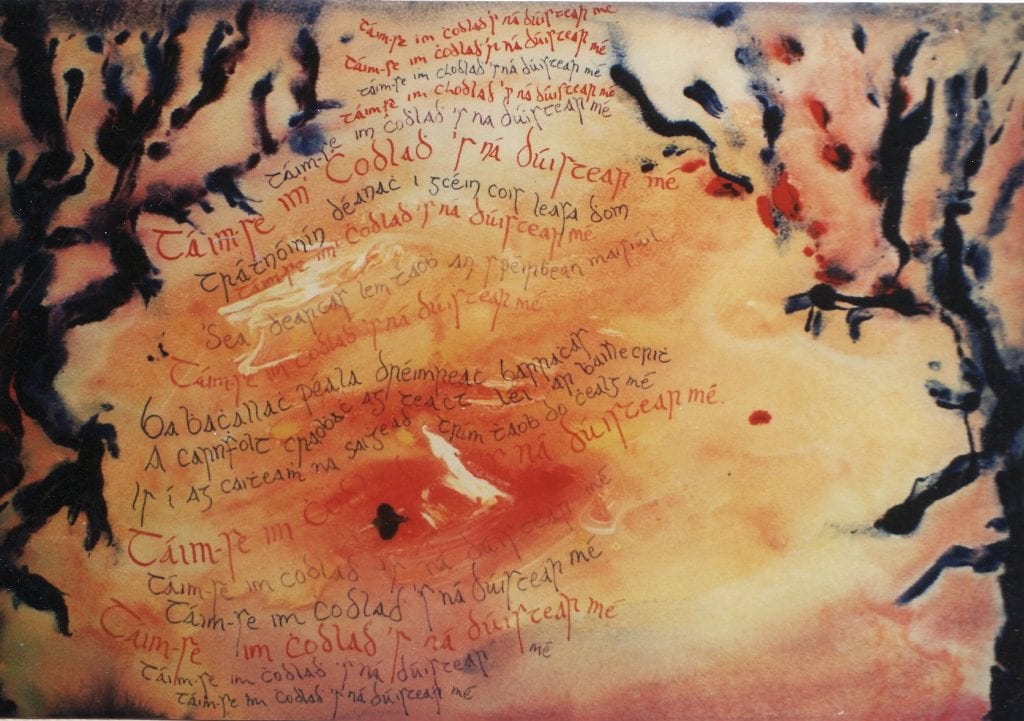

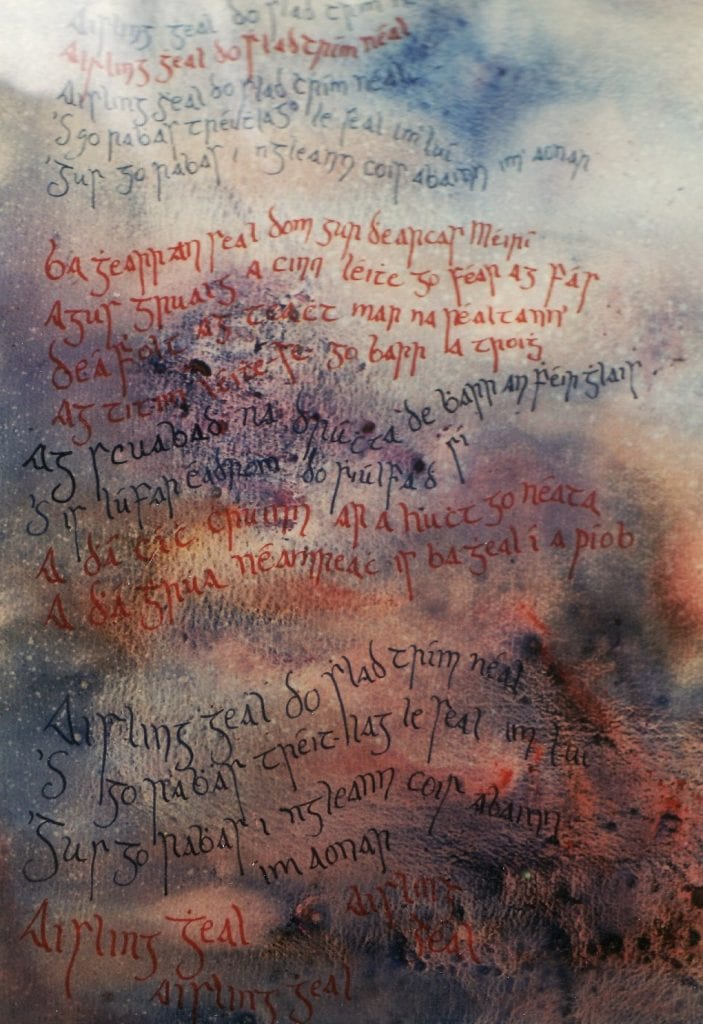

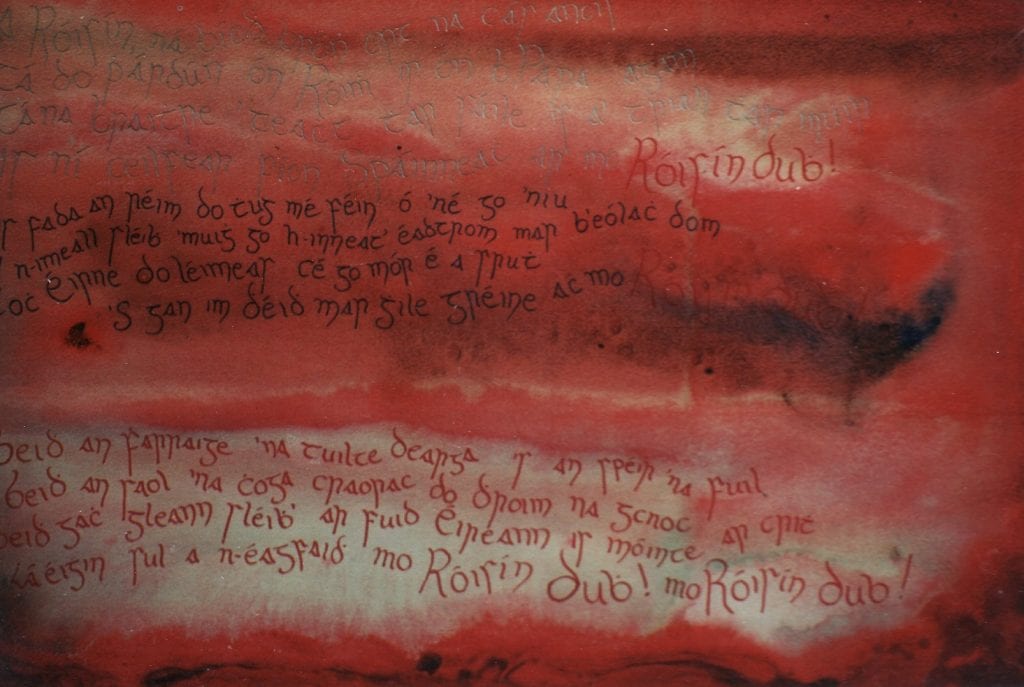

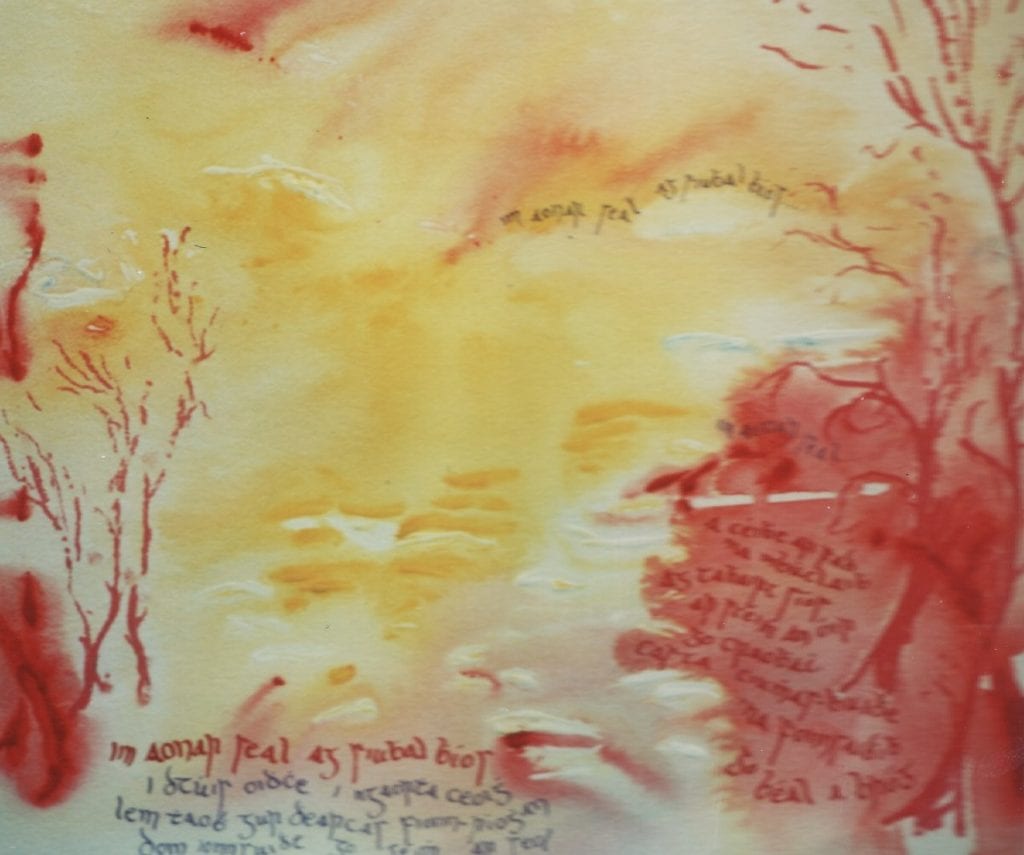

It is from this tradition that we get many of Ireland’s melodic gems, such as “Róisín Dubh”, “Im Aonar Seal”, “Aisling Gheal” and “Táimse im Chodladh”.

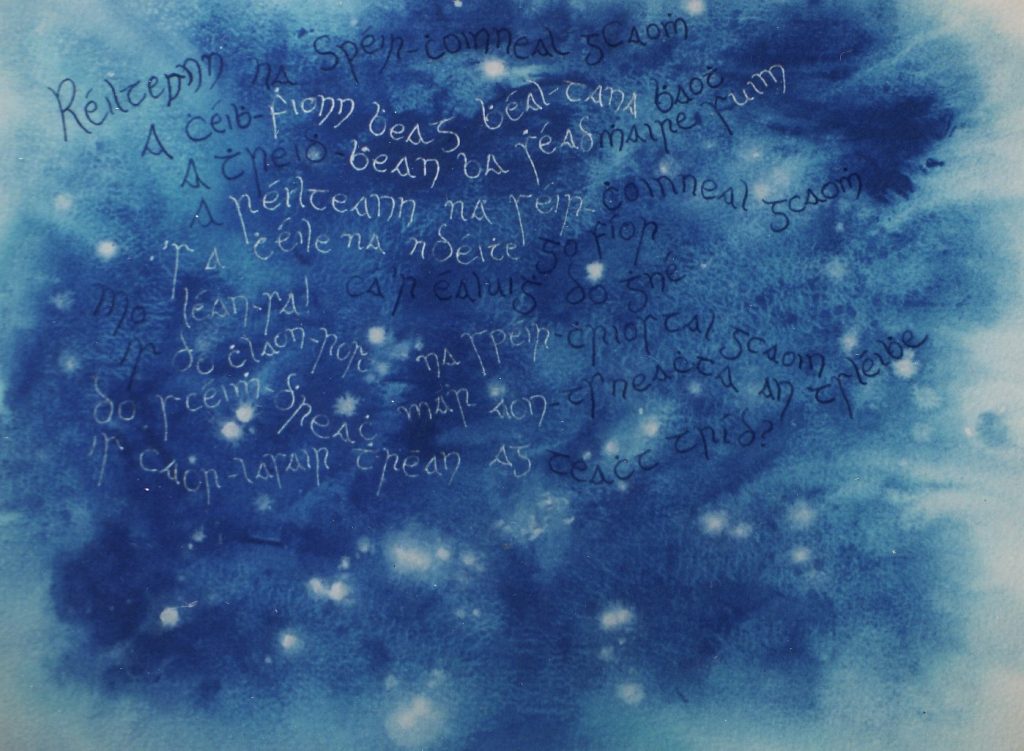

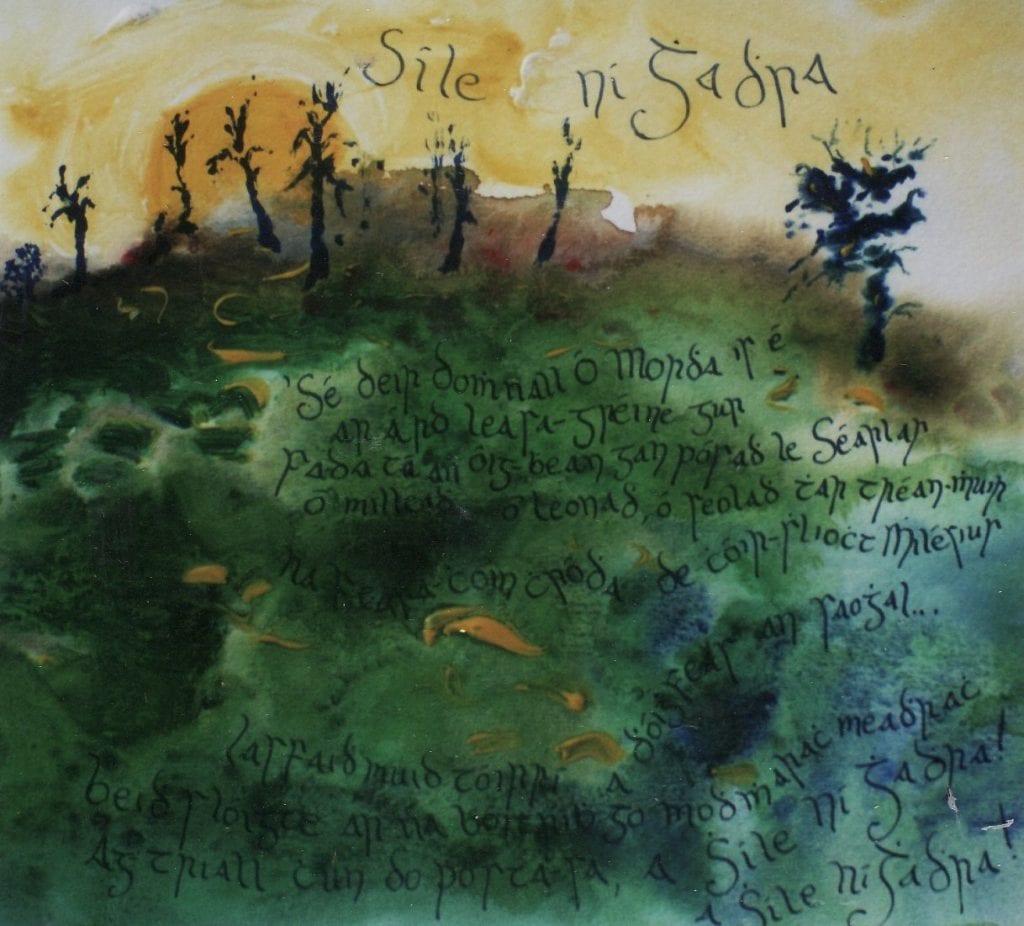

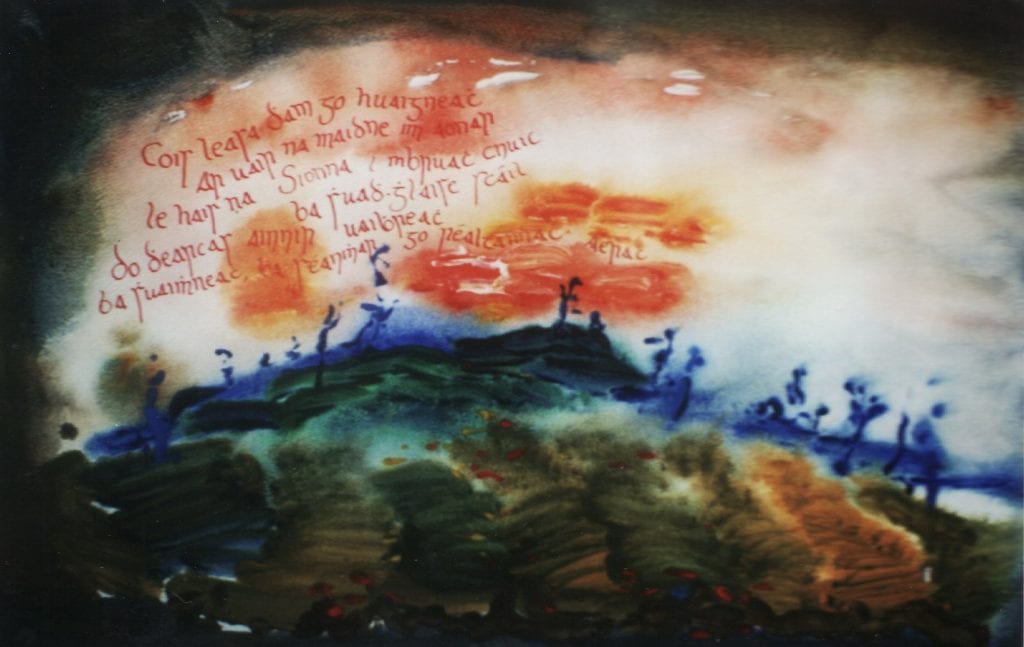

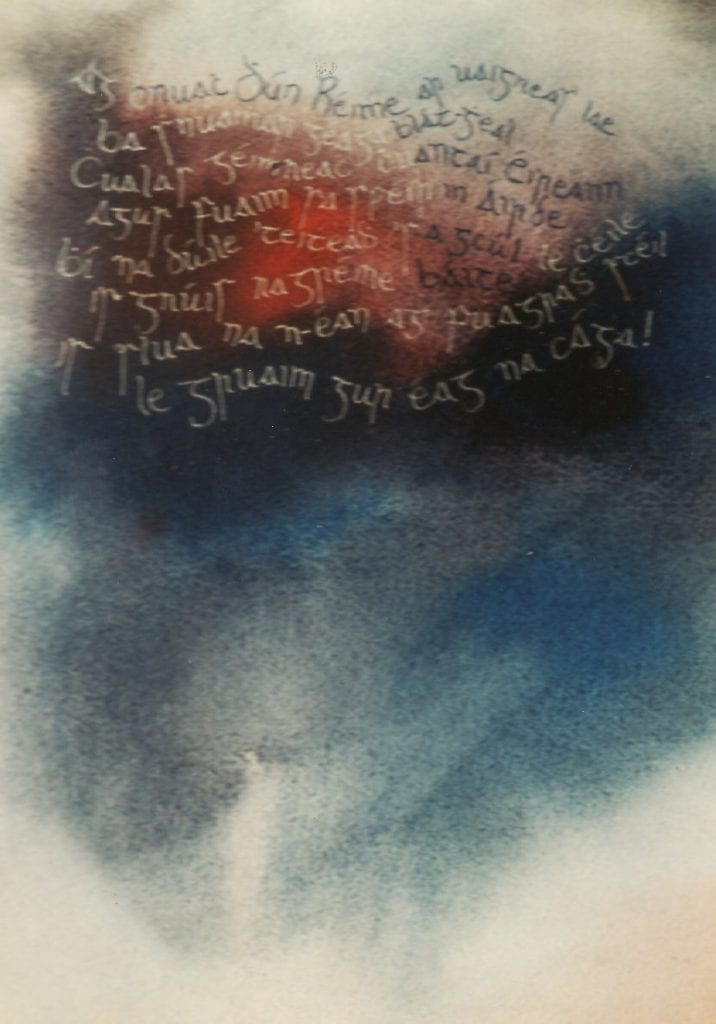

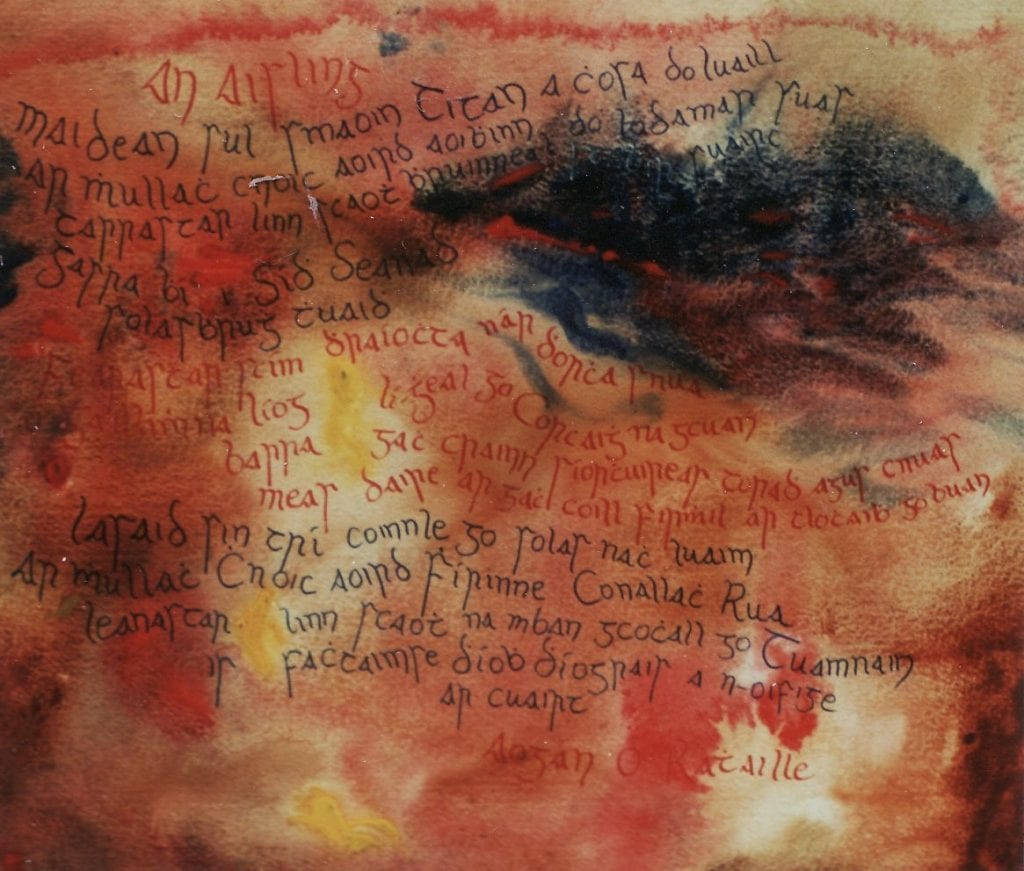

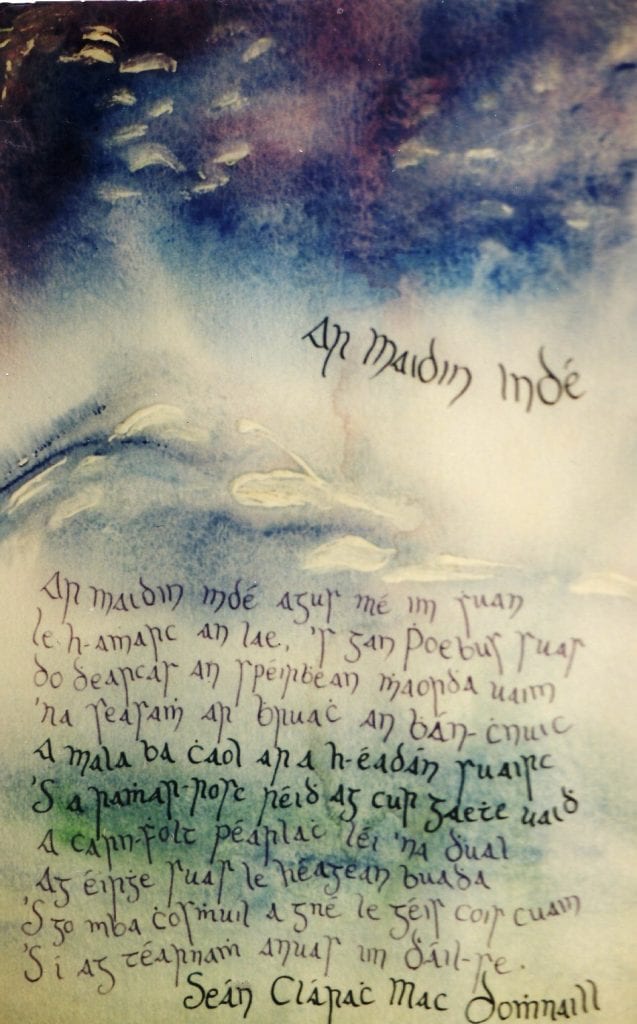

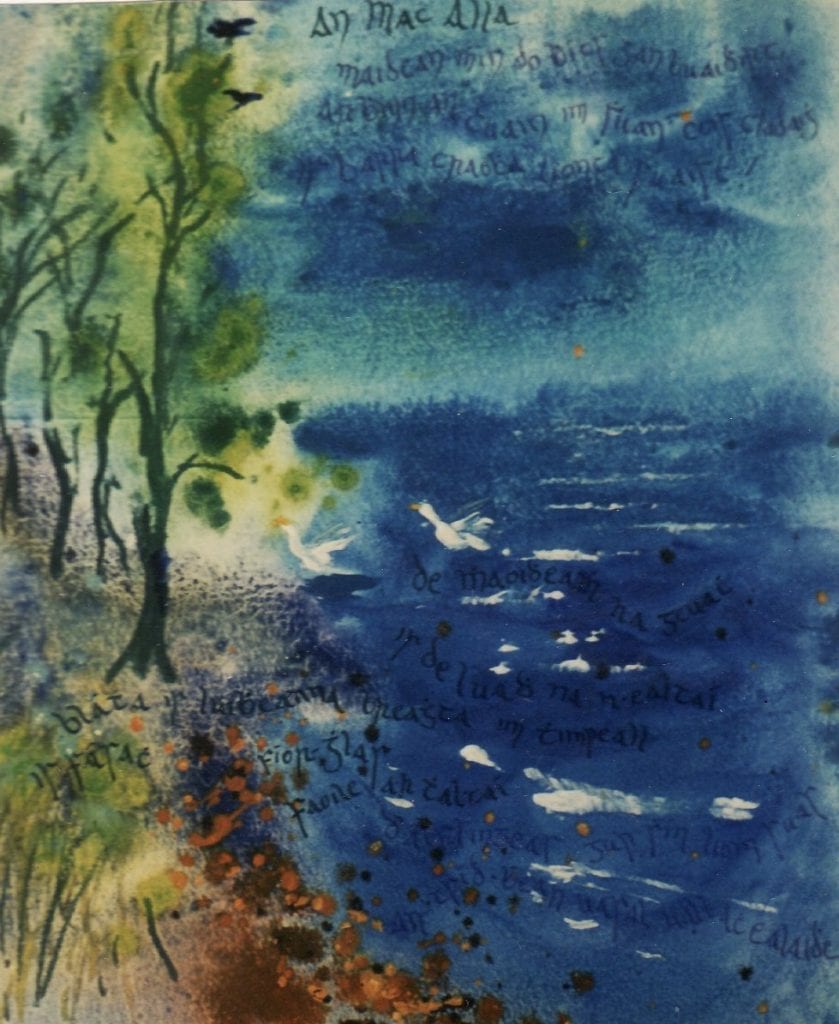

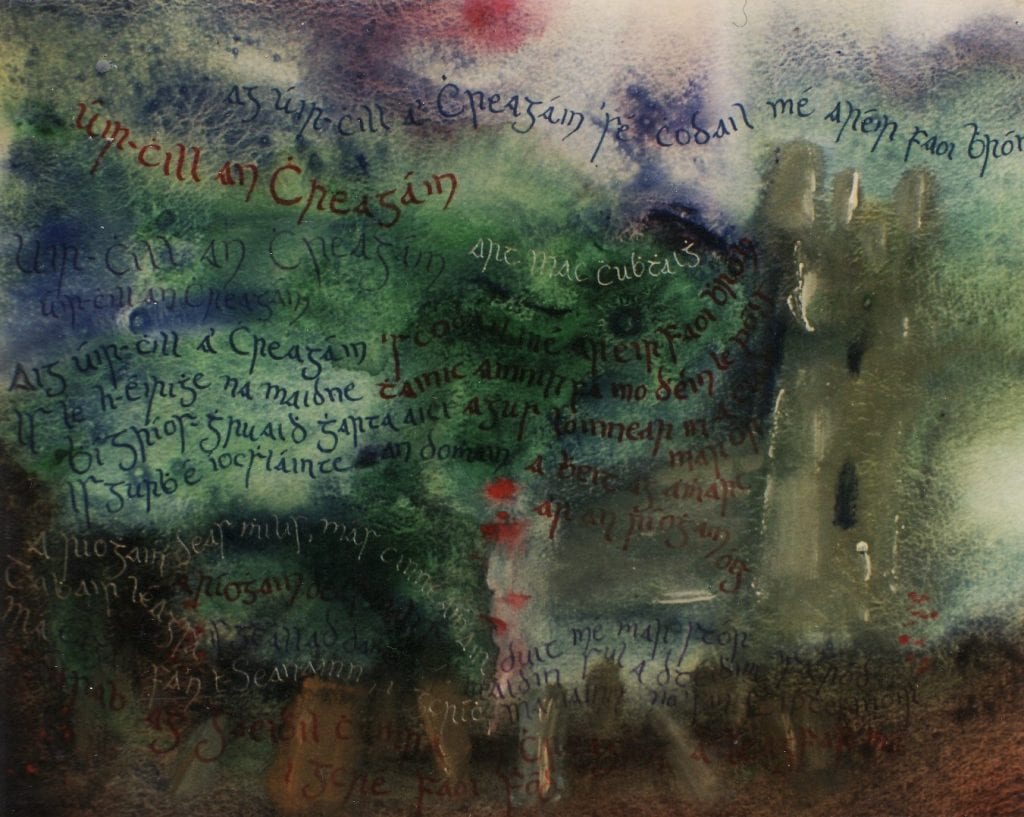

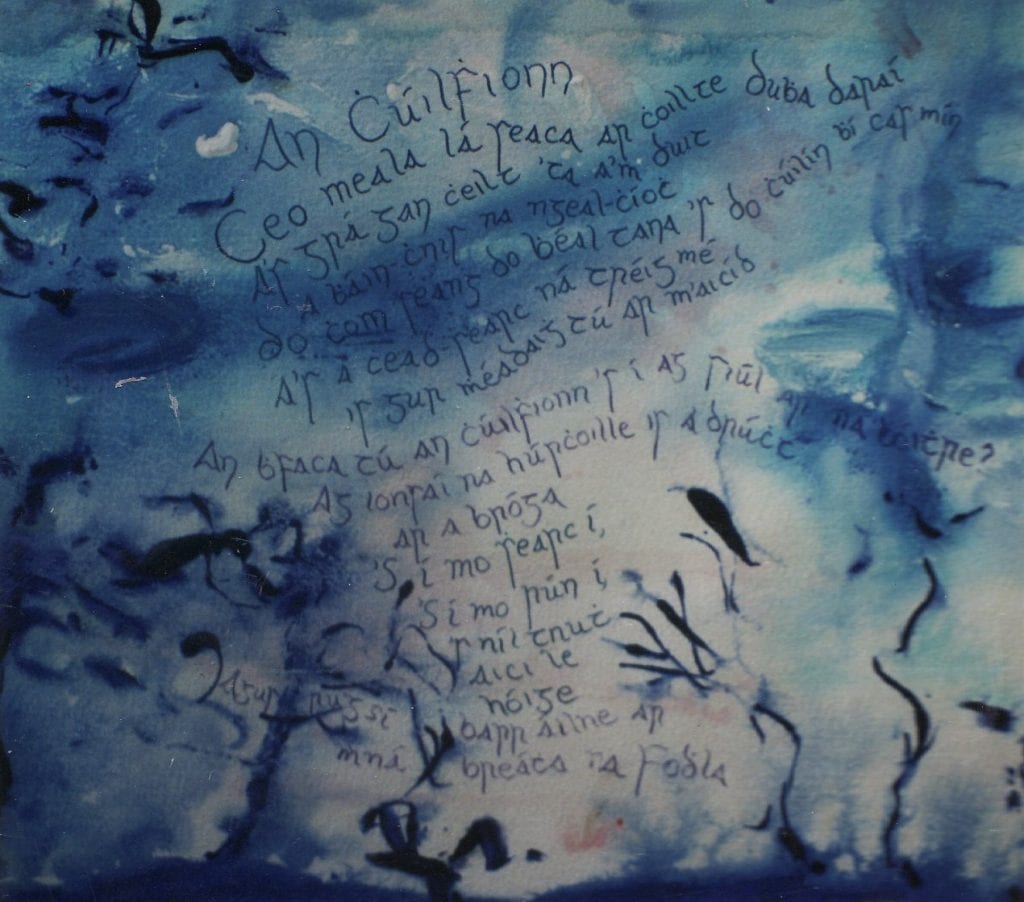

The aisling was essentially a vision of a beautiful woman, often in distress, who represented the soul of Ireland. The poet falls asleep in his bed, or by a river, or on a fairy fort, and in his dream he sees this vision, and then describes the lady’s attributes in colourful, adjectival language. There then follows, usually, a prophesy of some kind, leaving the poet, and his community, more hopeful for the future.

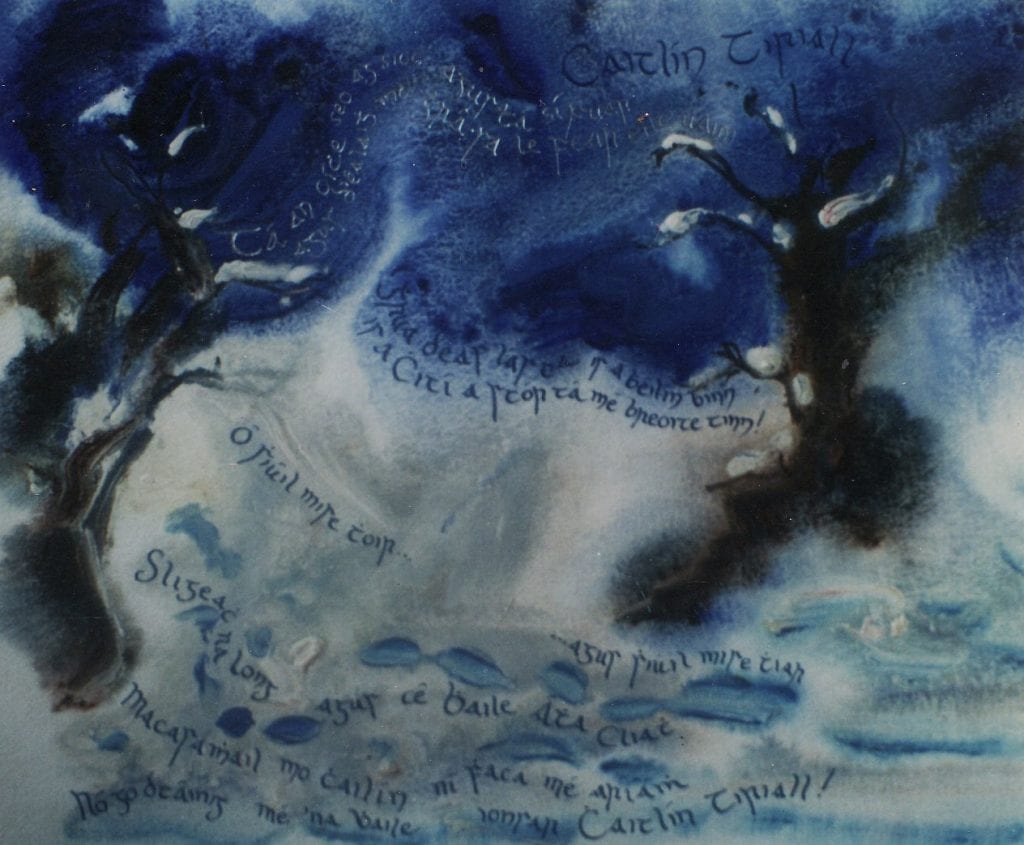

In another kind of song – not strictly an aisling – Ireland is given an allegorical name, like Kathleen Ní Houlihan [Caitlín Ní Uallacháin]. Since the name of Ireland was forbidden by laws imposed upon them by the English ruling classes of the time, the poets pretended to be writing love poems in honour of “a certain lady”, using all sorts of fictitious names. Occasionally, the woman was to marry Bonnie Prince Charlie, thus uniting Ireland with the Stuart dynasty and liberating both her and Scotland from English tyranny. There was also a suggestion of help from Spain in some of these songs. In others, Ireland was, in one case at least, represented by a bewildered cow driven into barren lands – “The Silk of the Kine” – and, in another, as a “Poor Old Woman” heralding long-awaited help from France. These songs were sung by generation after generation of Gaeltacht singers, right down to our own times, and can still be heard today in parts of Donegal, Mayo, Galway, Cork, Kerry and Waterford – wherever Gaelic is spoken.

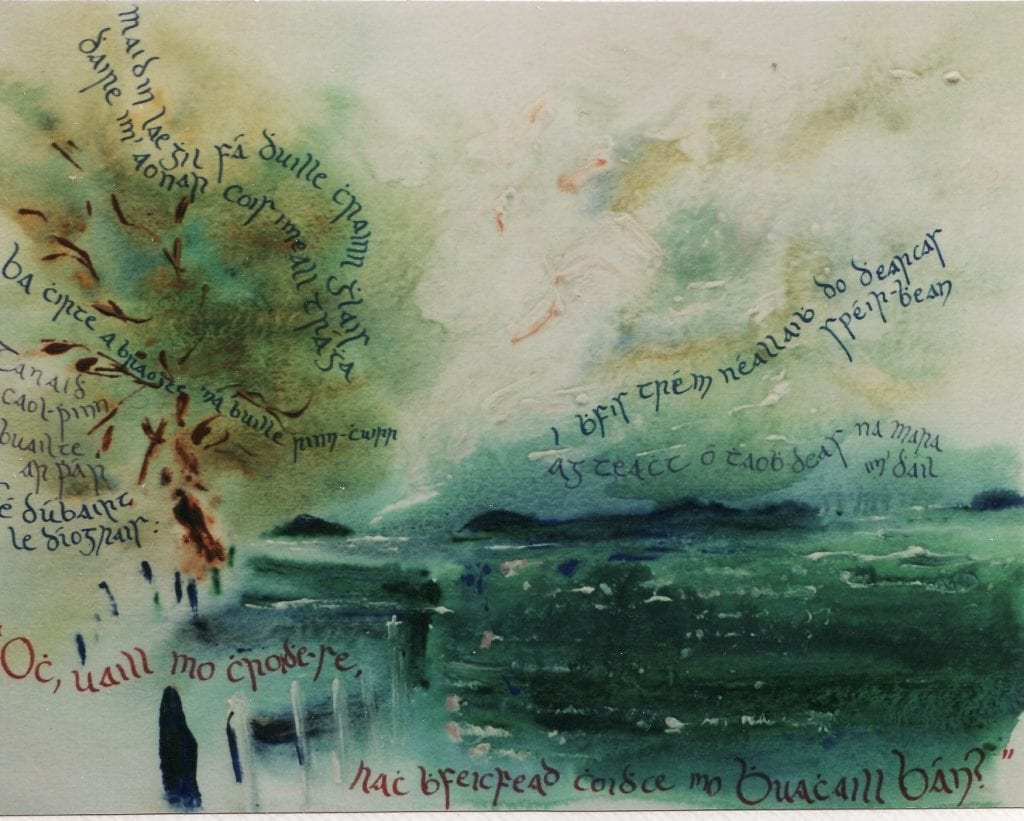

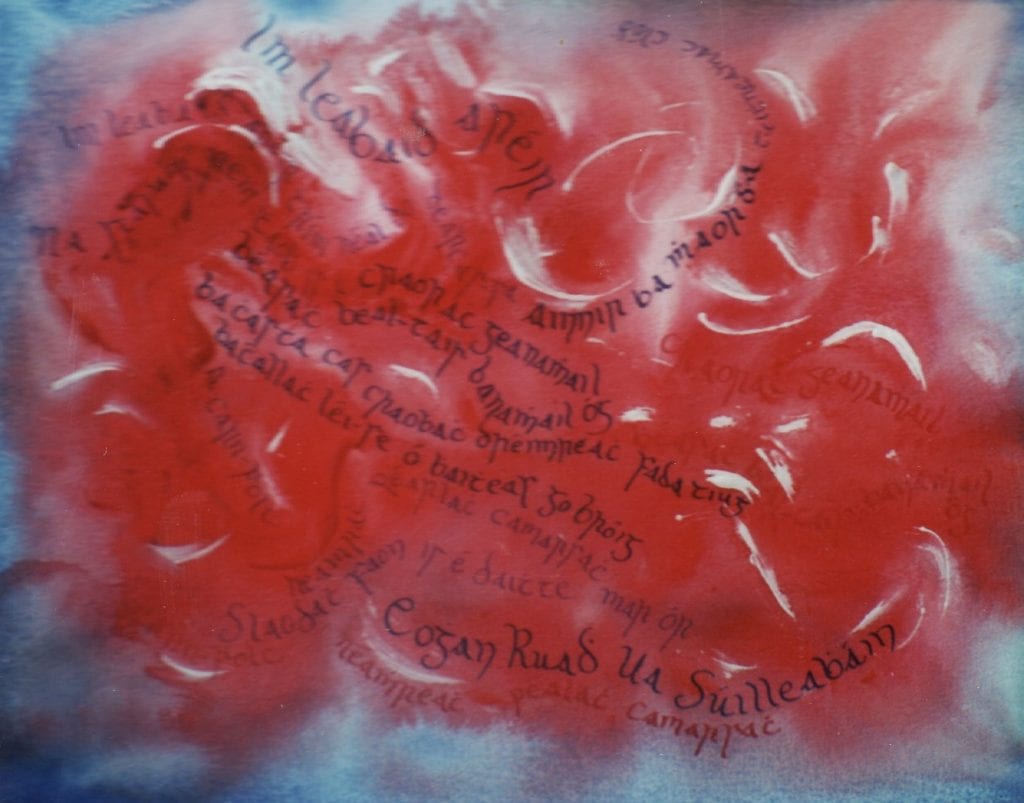

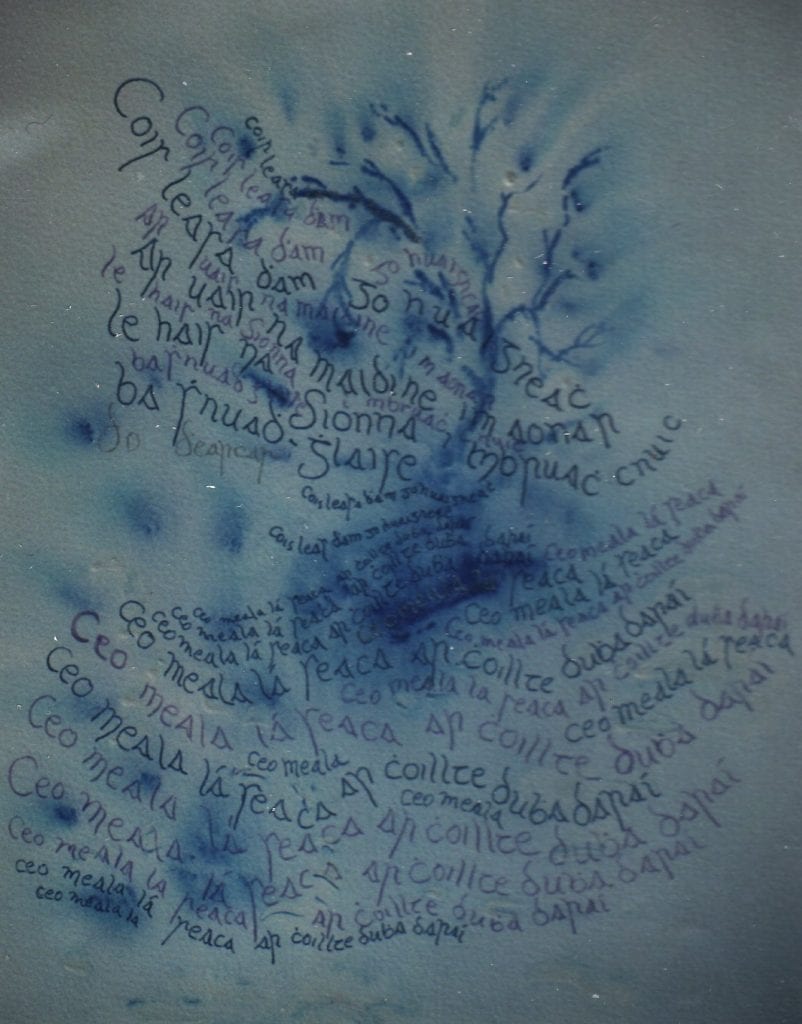

Apart from the extremely lyrical descriptions of the woman herself –her long-flowing hair, the radiance of her cheeks, her beautiful slender hands, etc. – the scene itself –that is, the poet within the landscape at the point of witnessing this apparition- was frequently set in a very “painterly” fashion, almost as if the poets were trying to evoke a landscape full of mystery and imagination, such as in the romantic scenes favoured by early 19th century artists.

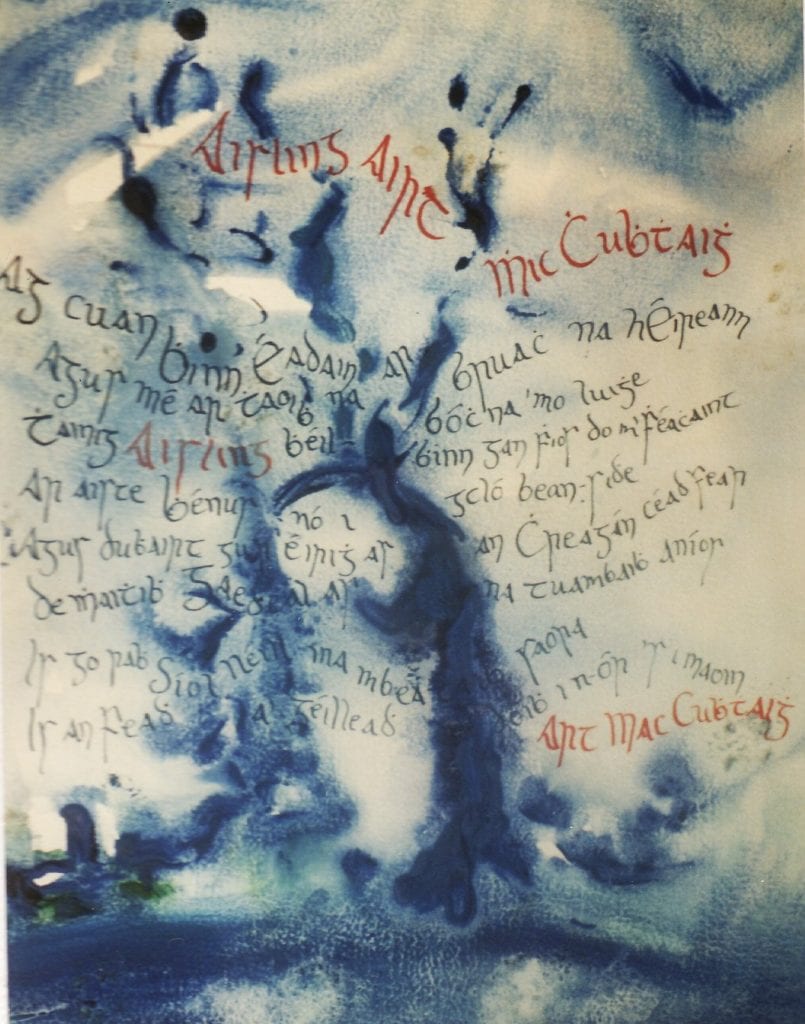

It is this latter aspect of the aisling which appealed most to Seoirse Ó Dochartaigh who has more of a leaning to the landscape than to the human figure. And although he admits to having a soft spot for Romantic painting, it is nevertheless 20th-century art techniques – from Post- Impressionism onwards -that he uses in this series.

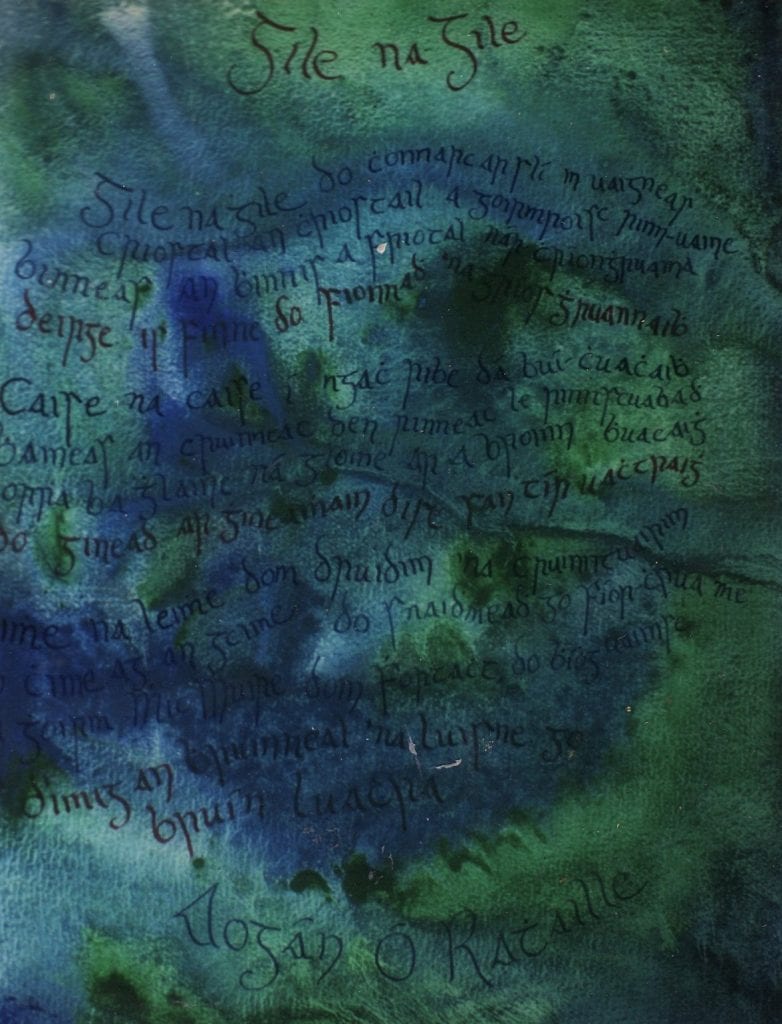

Another attractive feature of the aisling, although only tangential to the actual tradition, is the old Gaelic script in which the poetry was sometimes written down. The aisling, of course, was part of the oral tradition but local, unpaid scribes in the 18th and 19th centuries took it upon themselves to preserve the poems in manuscript and did so using a beautiful but quaint, rustic calligraphy.