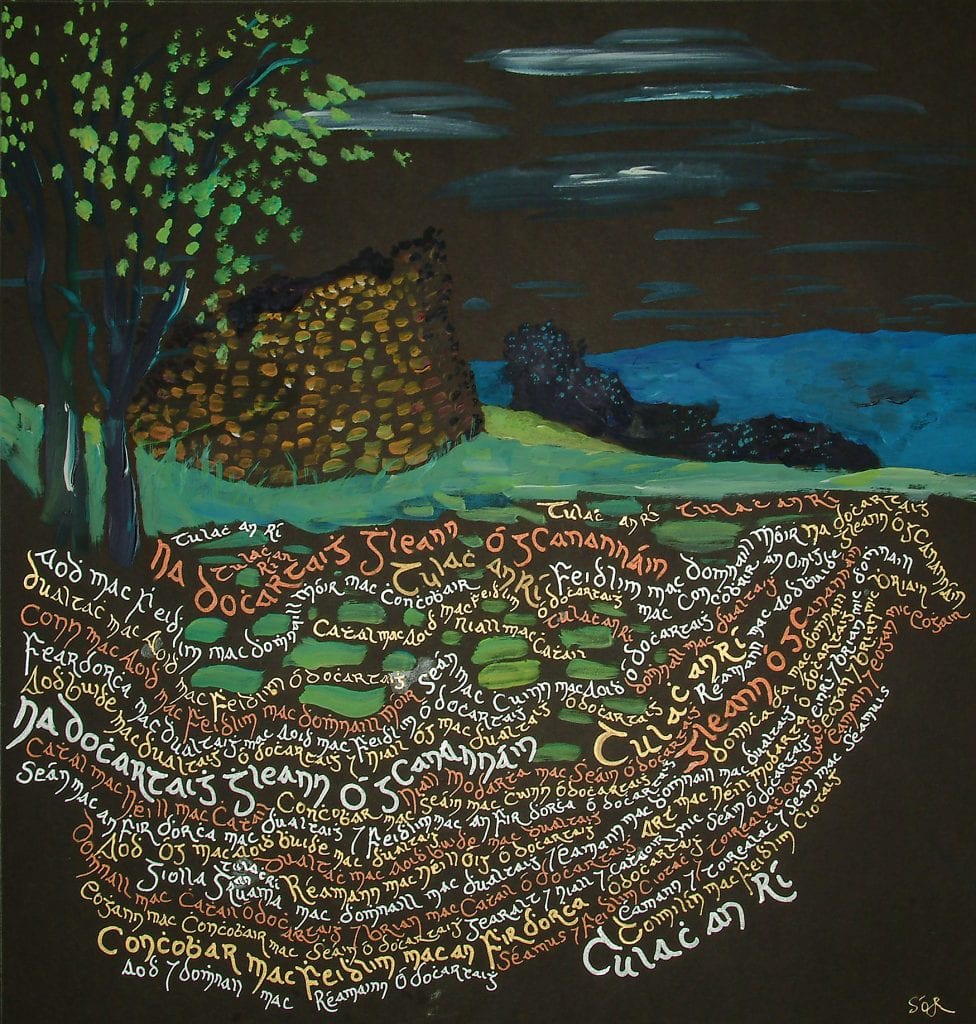

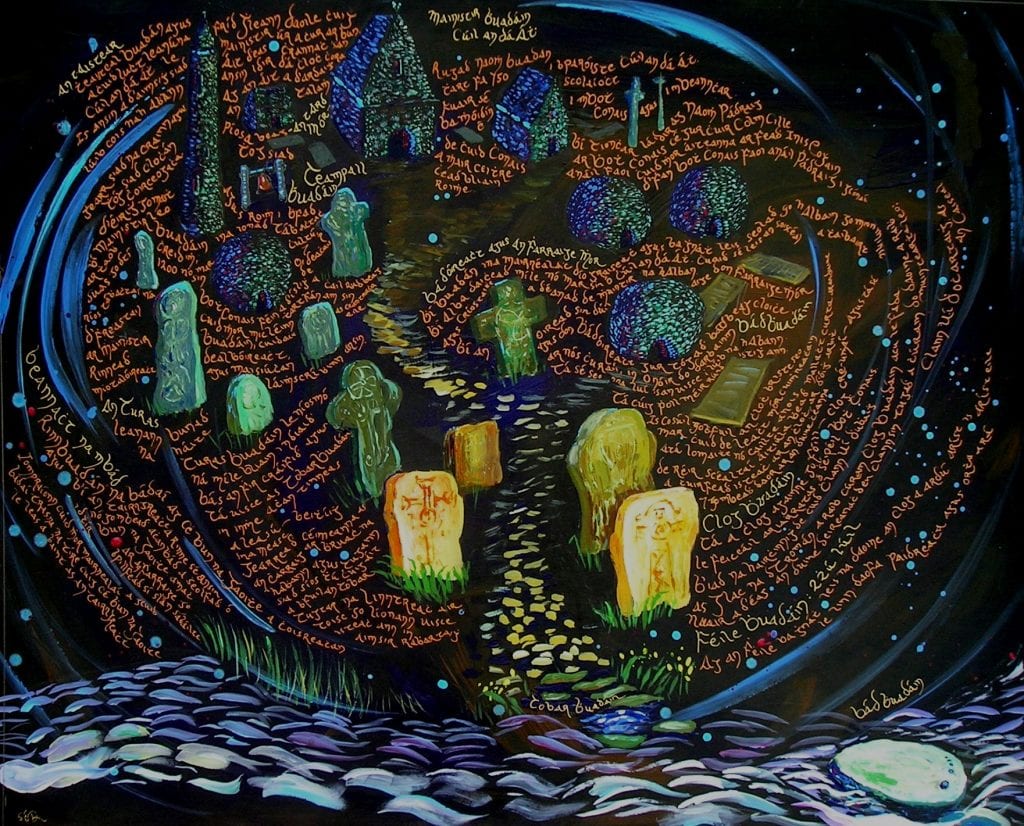

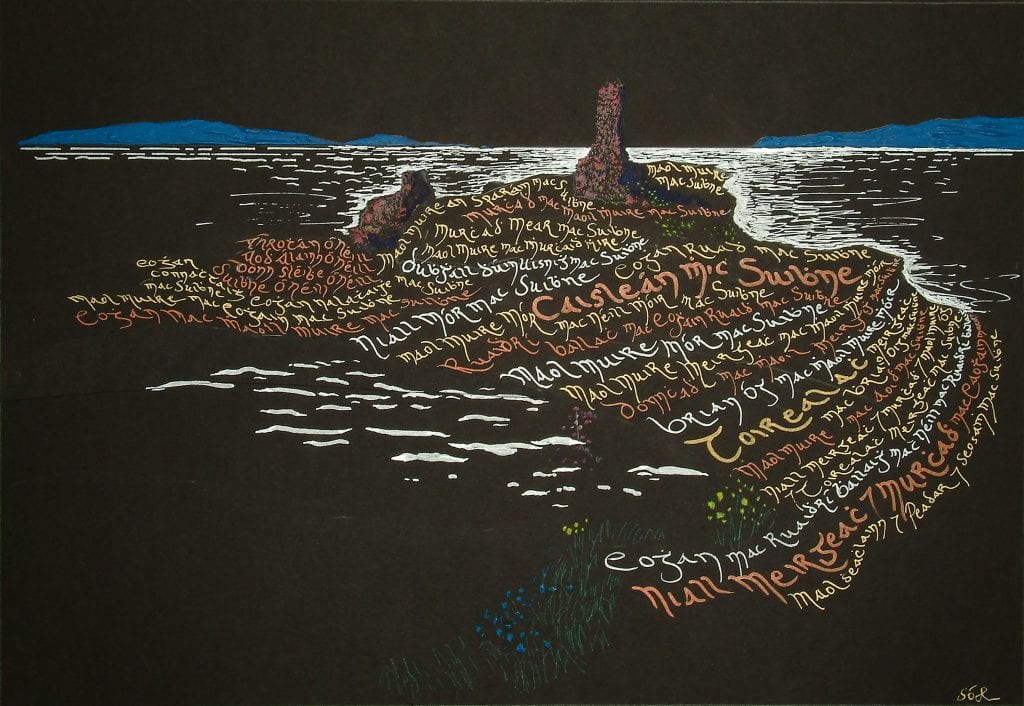

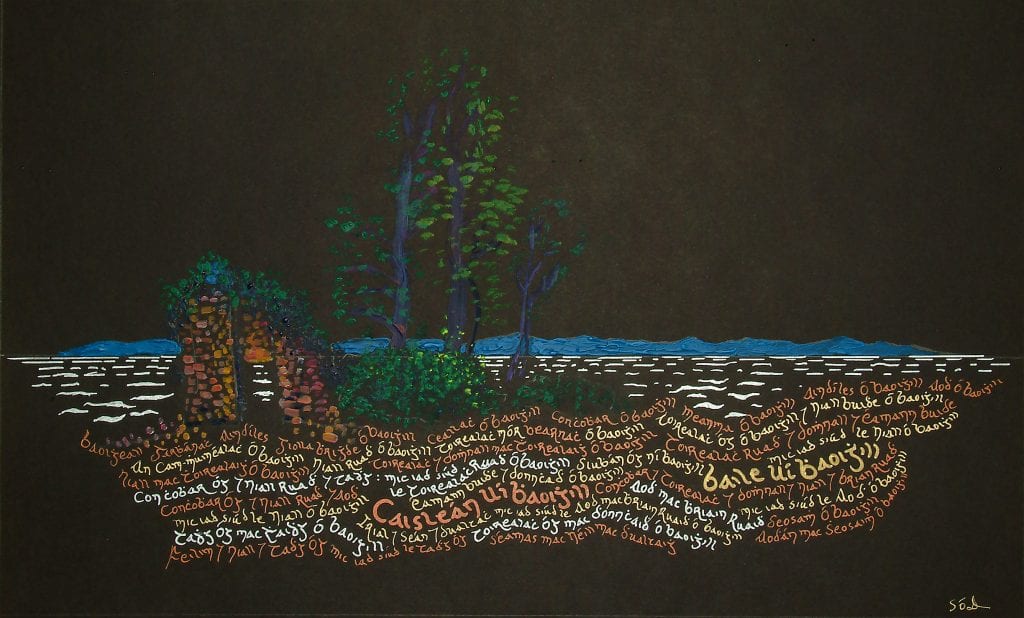

Calligraphy & Painting (1997-2007)

Calligraphic Insertions

Chinese Traditional Painting, and some Islamic art, often involves the insertion of texts into the work to form part of the composition. Calligraphic painting by the contemporary Indonesian artist Kurnia Agung Robiansyah is highly skilled but leans towards graphic art rather than fine art.

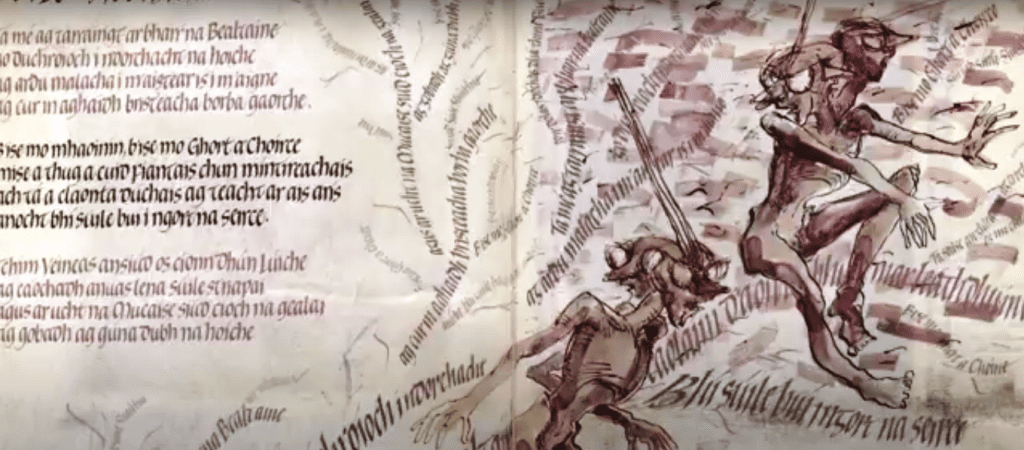

The Great Book of Ireland (Leabhar Mór na hÉireann) was a project which began in 1989. The book was published in 1991 and in January 2013 it was acquired by University College Cork for $1 million.

A huge volume of 250 pages of (510 by 360 by 110mm), the book brings together the work of 121 artists, 143 poets and 9 composers who painted, drew and wrote directly on the vellum. Calligraphy by Denis Brown to each opening serves to unify the book.

I began my journey in the 1992, the year after the publication of The Great Book of Ireland. When I started to insert calligraphy into my paintings I was not aware of this book’s existence. However, I knew I could make a connection with Italian Renaissance art however oblique that connection might seem.

Botticelli’s painting, “Mystic Nativity” [c.1500], took Renaissance representational art to, perhaps, its spiritual limits. The painting’s “other-worldliness” has undoubtedly given art historians good enough reason for the use of the word “mystic” in its title. However, the Botticelli work is ostensibly an outward, physical representation of the circumstances surrounding the birth of Christ. Its chief concerns therefore are with the immediate visible world.

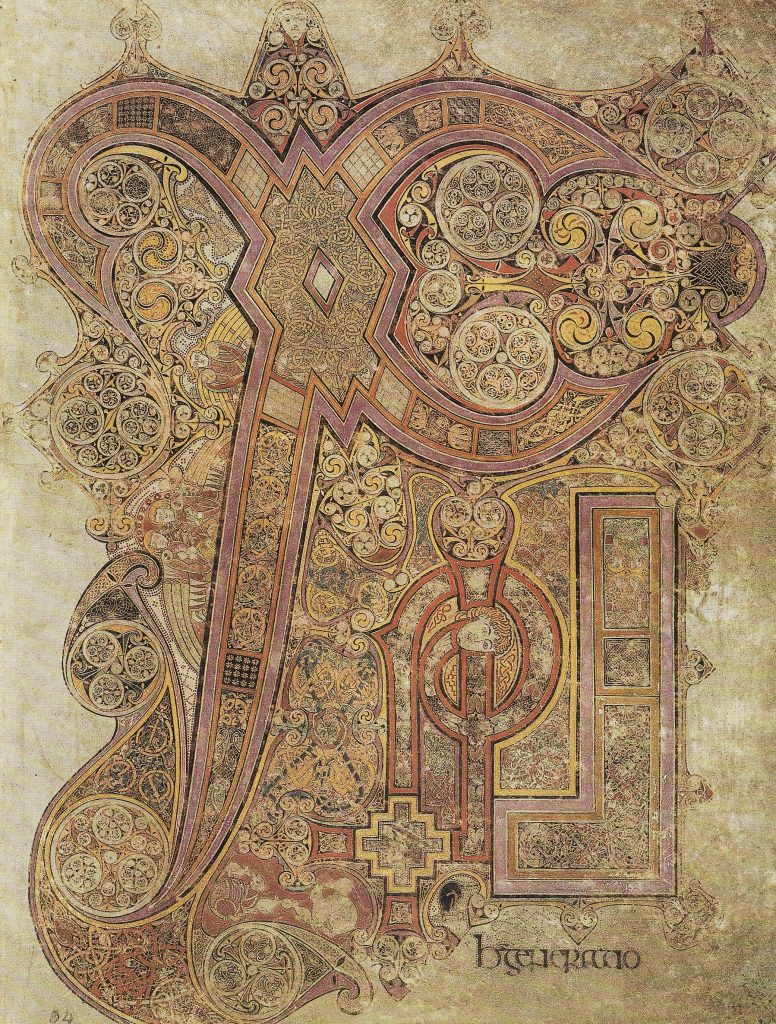

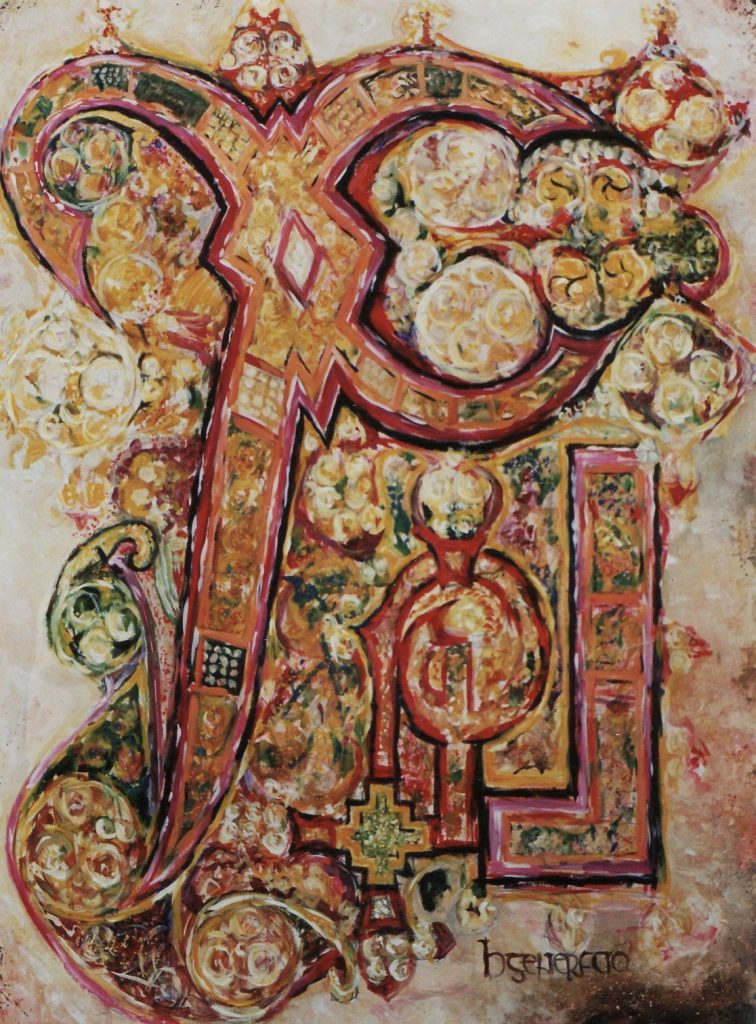

On the other hand, the anonymous Irish artist of the 9th century who painted the Chi-Rho page in the Book of Kells, a page which celebrates precisely that same event, had a totally different visual concept of the birth of Christ – almost an entirely abstract view. The Irish work is, arguably, more deserving of the title “Mystic Nativity” than the Botticelli.

But to understand this particular concept we need to look at Irish culture as a whole and as a continuum:

“The scribe, on his part, transformed the epic oral tradition into written

words and books, and thus gave visual life and permanence to the word

itself. Inspired by the patterns of the metal worker, the artist began to

decorate his letters almost beyond recognition…

The hoard of gold and the hoard of words, both enriched with their

supernatural symbols, were treasured and augmented by each succeeding

wave of invader-settlers. The Celtic artist saw all life in terms of creative

energy, not in terms of simple visual experience; thus the constantly

moving and regenerating spiral became the pictorial symbol of the endless

cycle of death and rebirth… The exuberance and exaggeration of such Irish

masterpieces [as the Chi-Rho page] demonstrate the quality of the Irish

imagination – flowing freely but within the clear bounds of intellectual

control – which could create a fantastically real dream world as precise

and as brilliant in line and colour as gold filigree or millefiore enamel, and

as plausible as any visual image of the sensate world”

(Marilyn Stokstad “The Art of Prehistoric and Early Christian Ireland” [1976])

The Book of Kells, known in the Middle Ages as “The Great Gospel Book of Colm Cille”, was completed in the 9th century. Four distinct styles have been detected in the making of the book, suggesting that it was the work of at least four illuminators. One was identified as “The Goldsmith”, on account of his fondness for the jewel-like quality of his decorations. Among the pages attributed to him is the “Chi-Rho” page.

A thicket of typically Celtic, gem-like ornamentation dominates the whole page. Greek letters symbolise the name of Christ: a huge “chi”, outlined in black and lavender, and a small “rho”, similarly rimmed with red.

XPI hgeneratio is the monogram used in the page– a mixture of Greek and Latin.

XPI [Chi-Rho] = Christi

h= autem

When viewed in the correct order, it becomes:

Christi autem generatio = “the birth of Christ”

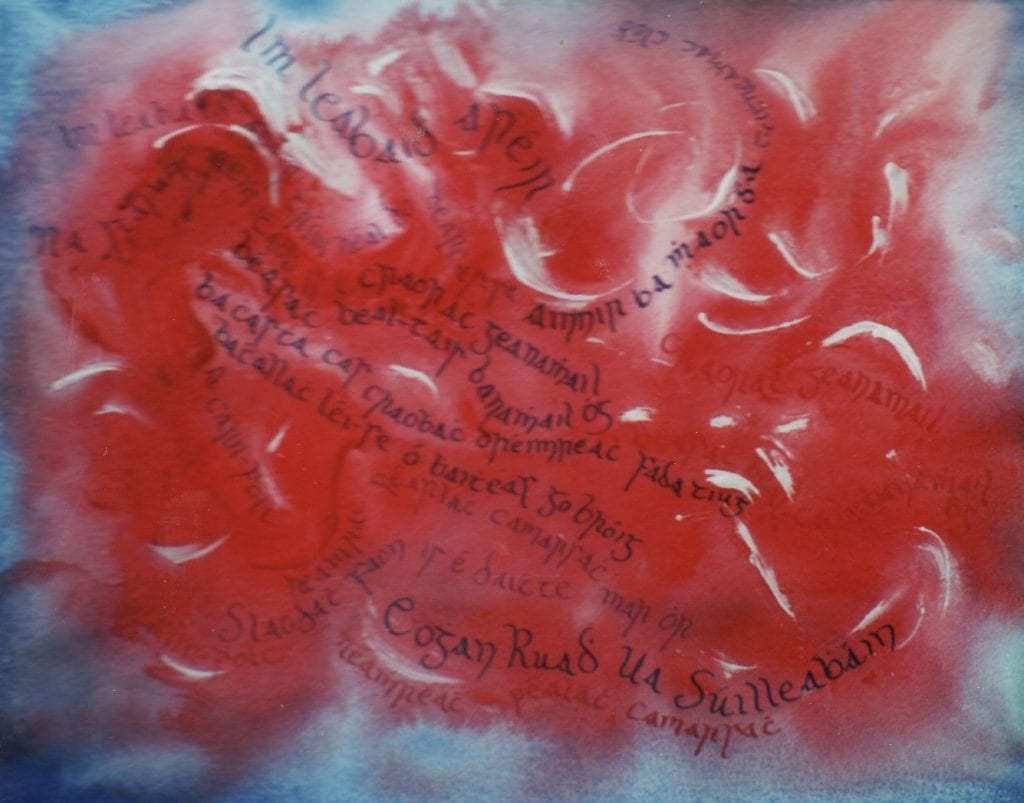

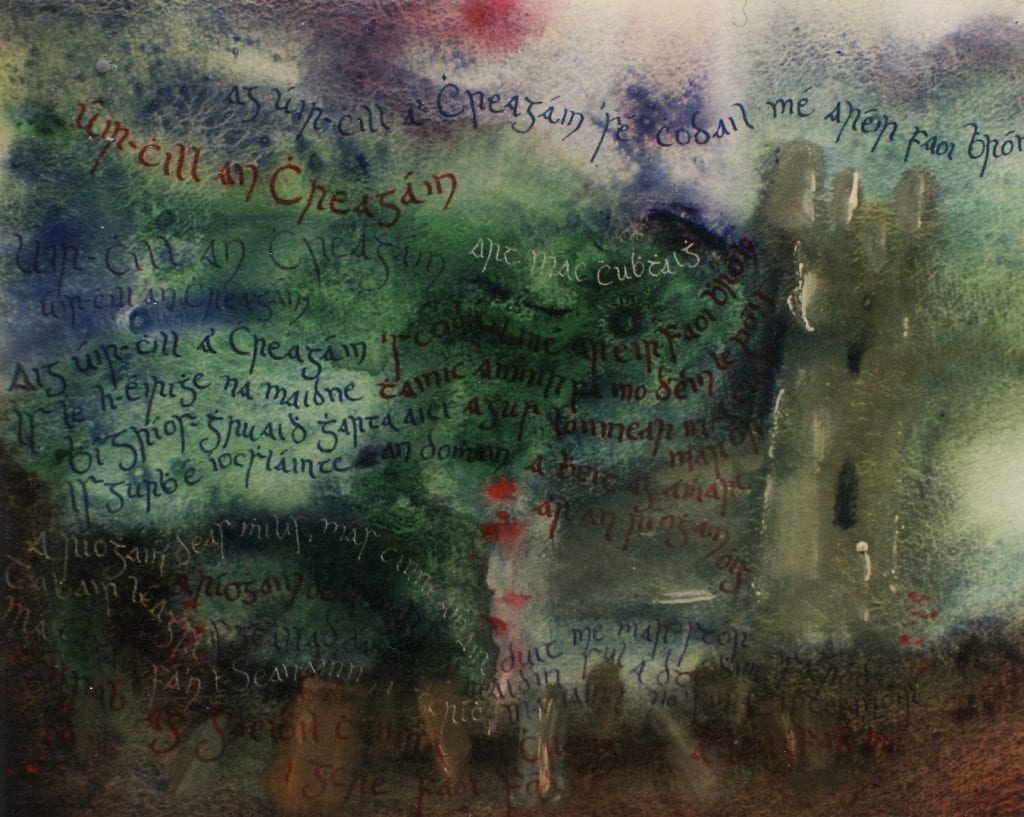

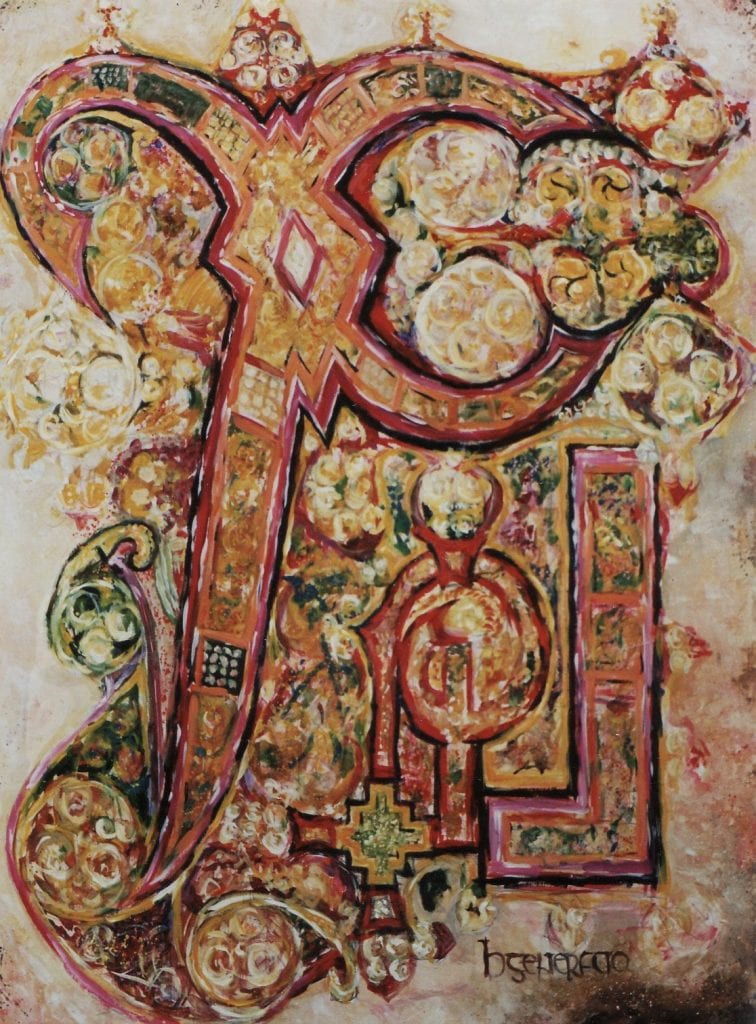

Breith Mhisteach Chríost (1995)

– A modern interpretation by Seoirse Ó Dochartaigh

I have tried in my own painting to freely interpret Ireland’s “Mystic Nativity” by reinventing an earlier Irish/Celtic aesthetic whilst applying certain painting techniques used by some of the 20th century American Abstract Expressionists who were constantly in search of a new spirituality: Jasper Johns, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. Their search, like mine, wasn’t necessarily within the confines of conventional religions. This work (Breith Mhisteach Chríost, Christ’s Mystical Nativity) was featured in the Oireachtas Annual Art Show held in the Waterfront Hall, Belfast in the 1990s. It is now on display in Scoil na Mainistreach, Donegal Town.